Description

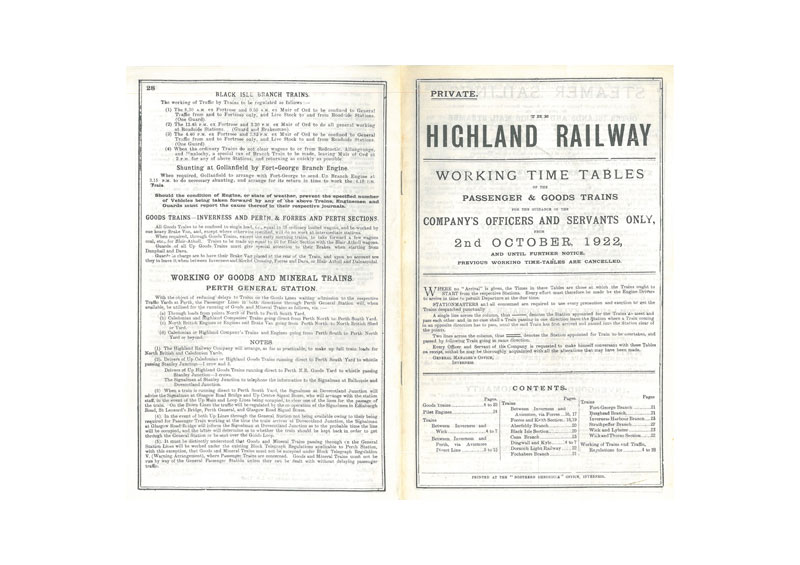

Almost four years after the Armistice which ended the Great War, the Highland is still struggling to recover from the immense strain placed upon it. Until 1914, it was predominantly a holiday line- busy for 10-12 weeks in late summer, early autumn, when everything with wheels was in use. For the remainder of the year it ran basically a “winter” timetable concentrating on track repairs and renewals, and station and rolling stock maintenance. This was also a peak period for its main freight traffic – sheep and timber. In the Great War the Highland became the main route for supplying fuel and ammunition to the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, the R.N. Dockyard at Invergordon, naval and army camps at Nigg, Cromarty Tain, Dornoch and Dunrobin. Associated with all these after transporting construction materials, there were thousands of troops and sailors to transport. All this over a basically single line railway, with passing places and a few miles of double track.

By the end of August 1915, the Highland was in dire straits. Little or no track maintenance had been done, resulting in more frequent breakdowns amongst locomotives which also were in need of attention. Of 152 locomotives in stock 50 ere in such poor condition that they had to be withdrawn, while 50 others were badly in need of repair, but had to be kept at work. The Company’s Works at Lochgorm were understaffed because so many men had joined up and it had also been tasked with vitally urgent munitions work. Locomotives sent to private firms for repair would be out of service for a year, because the firms also had priority munitions work on hand. An appeal was made to the Railway Executive Committee, which was running the nation’s railway on behalf of the Government . This body comprising the General Managers of the leading Railway Companies, most of whom were also in difficulties, but out the outbreak of war had some spare capacity, sent the Chief Mechanical Engineers or Locomotive Supts. of the L.N.W.R,, G.C.R. Caledonian and LBSCR to meet Highland Chief Officers at Perth. All had already sent locomotives to France, because our gallant Allies could not, or would not provide them for moving BEF troops and supplies, despite the fact that quantities of rolling stock and engines were held in reserve south of Paris, in case evacuation of the City should prove necessary. The Railway Executive Committee arranged the loan of 20 locomotives, and exceptionally, the Highland was allowed to place orders for a few new locomotives from private builders, for eventual delivery.

By autumn 1916, the railway was additionally suffering an acute shortage of wagons, because of the huge increase in the demand for timber, for pit props, trench construction at the front and building of new camps. Some 850 wagons were lent by other companies. Even the Armistice brought little relief, . In the winter of 1919/20, many stations had between15,000 and 40,000 tons of Government traffic waiting to move – and this ignores the increasing volume of civilian traffic waiting.

Government control was extended after the Great War to 15th August 1921, so when this timertagle was introduced, The Highland had been master in its own house for a little over a year, but the effects of war, particularly in terms of shortage of engines are manifest in the restrictions on train loads to reduce pilotting, the astonisshing number of “mixed” trains which had to be run, and the comparatively small number of passenger trains which could not be used for shunting at intermediate stations.

It is interesting to compare this document with:-

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.